Trauma and the Brain

Trauma is a hot topic these days, and is both well-researched and often misunderstood. There's a lot of debate about what exactly qualifies as a traumatic event, and sometimes the term gets tossed around so much that it loses its meaning. On the flip side, being too rigid about defining trauma can also lead to overlooking genuine experiences and adding to the stigma around mental health.

What is trauma?

Trauma encompasses more than just the events themselves; it's also about our individual response and the context in which it occurs. Some conceptualize trauma as "Big T Traumas," encompassing major life-threatening events, and "little t traumas," which include smaller, more insidious experiences that slowly erode our sense of safety over time. This framework reflects the diverse range of experiences that can lead to trauma.

Additionally, vicarious trauma—experienced by individuals indirectly exposed to traumatic events—is a well-documented phenomenon. For instance, first responders, therapists, and family members of trauma survivors may all experience emotional distress as a result of their exposure to trauma.

Social connection also plays a significant role in the development and aftermath of trauma. Trauma often involves a sense of isolation or lack of social support, which can exacerbate its effects. The inability to connect with others during and after a traumatic event increase the likelihood of the development of trauma. In this regard, trauma can be about what happened to us, and can also be about what didn’t happen for us.

In regard to processing and validating trauma, where we readily accept physical pain as a reality of life, and can see and validate physical traumas such as broken bones or major medical events, we aren’t as quick to accept and validate emotional pain. Because we can’t readily see how the brain is reacting emotionally to stimuli, whether it is objectively life threatening or not, we assume it isn’t real, it’s less important, or we’re making a big deal out of nothing. Although they have different origins and mechanisms, emotional pain can be as distressing as physical pain. However, without physical markers, emotional pain is often left unattended.

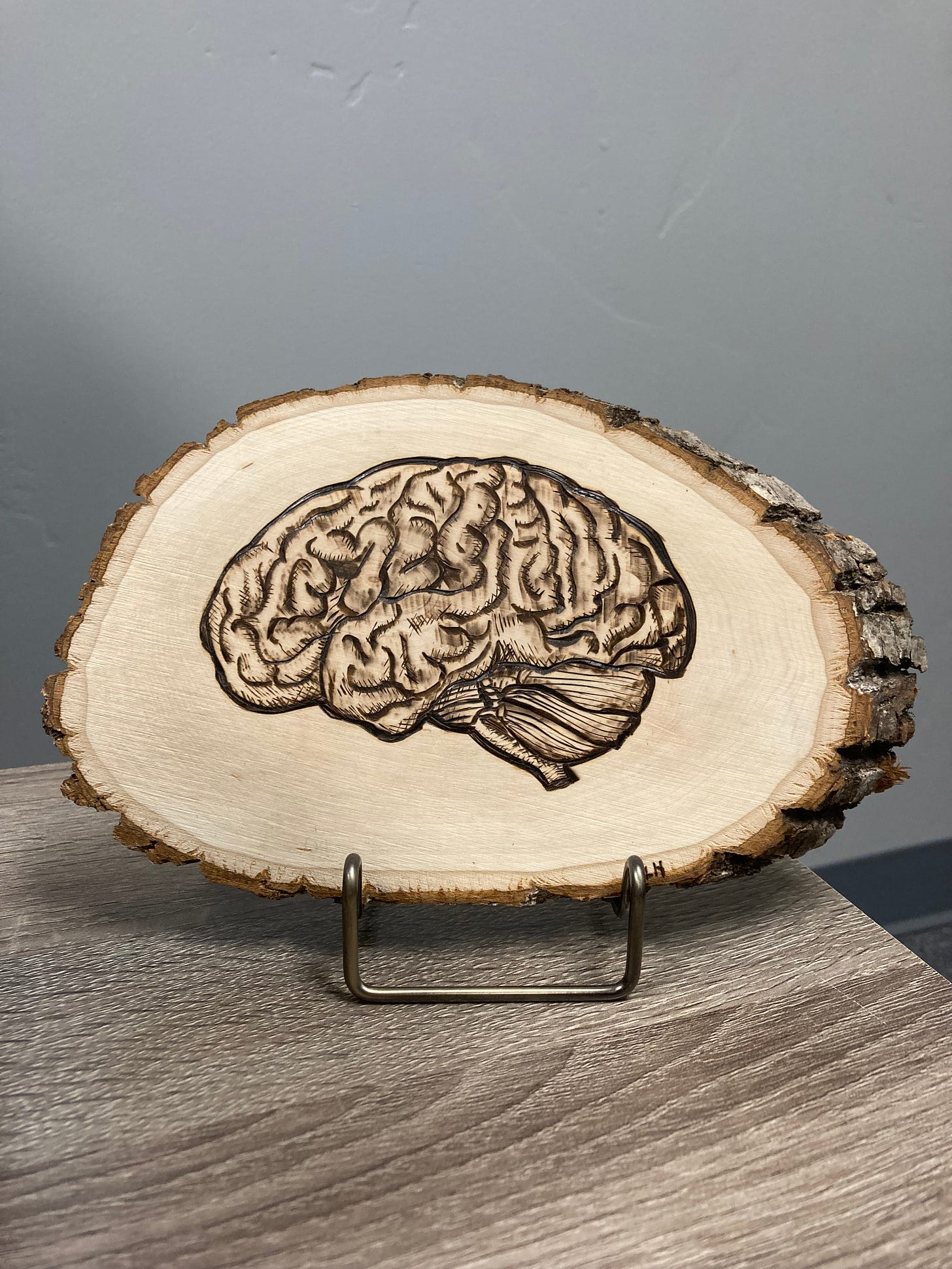

This is a wood burning of the brain courtesy of my husband. In this rendering, the brain stem is on the right, the frontal lobe is on the left.

Brain Development

The brain indeed develops from the bottom up, starting with the brain stem, which is connected to the spinal cord, and progressing up to the frontal cortexes located behind the forehead. As the brain develops upward, it becomes more advanced in its functions. While the majority of brain development occurs in utero, it continues to evolve throughout life.

At birth, the brain already possesses around 100 billion neural connections. During peak development, this number increases to approximately 100 trillion neural connections, which are crucial for the brain's function, speed, and complexity.

From birth to around age 5, the brain experiences significant growth in volume. Between ages 7 and 17, while the brain remains roughly the same size in volume, there are intense changes in the distribution of grey and white matter. During this period, new pathways are formed, enhancing the brain's capacity and functionality.

The frontal cortex, responsible for logic, reasoning, planning, and decision-making, undergoes significant development during childhood and adolescence. However, full maturation of the frontal and Neo-frontal cortex typically occurs in the late 20s to early 30s. Even into late adulthood (ages 20-70), the brain continues to exhibit plasticity, and the volume of grey matter may change.

Hormones also play a crucial role in brain development. However, the impact of natural changes to hormones (such as menopause) on brain function and structure is not yet fully understood due to limited research in this area.

Given that the brain evolves throughout life, it's reasonable to assume that traumatic events may affect individuals differently depending on their stage of development. These events can potentially influence brain development and functioning, highlighting the importance of considering developmental factors in trauma therapy and interventions.

Some Brain Basics: Brain Stem, Limbic System, and Frontal Lobes

The brain stem is dedicated to ensuring survival. Its primary function is to regulate automatic processes vital for life, such as breathing, heart rate, digestion, circulation, and blinking. These functions are largely involuntary, meaning we have limited conscious control over them. While we can consciously alter some of these processes temporarily, eventually the brain stem takes over to ensure our survival.

The brain stem communicates with the entire body and other parts of the brain, including the limbic system. The limbic system, located in the midbrain, is responsible for processing emotions and detecting threats. A key component of this system is a small, almond-shaped organ called the amygdala. The amygdala's main role is to assess information from the environment and signal to the brain stem how to respond emotionally. It determines whether we need to be on high alert, whether we can relax, or if our basic needs are met. The amygdala communicates through physiological sensations interpreted as emotions, playing a crucial role in our safety responses.

Contrastingly, the frontal lobe is the brain's center for higher cognitive functions, including awareness of time and space. It's the only part of the brain that is fully conscious. Surprisingly, it's active for only about 5% of the time, processing roughly 50 pieces of information per second. This means that most of the time, we rely on lower-level brain regions for impulse, instinct, and learned behaviors. In stark contrast, the amygdala processes an astounding amount of information—about 11 million pieces per second—searching for cues of danger or safety. It rapidly categorizes and communicates this information through physiological cues, shaping our responses to the world around us.

Fight/Flight Response

When the amygdala perceives a threat to our safety, it triggers the activation of the body's fight or flight response. This involves a cascade of physiological changes designed to prepare us for immediate action. The amygdala sends signals to the brain stem and other brain regions, initiating a series of rapid responses.

First, it prompts shallow, rapid breathing to optimize oxygen delivery to the muscles for increased efficiency. Simultaneously, it elevates heart rate and circulation, directing blood flow away from non-essential organs and towards the muscles to provide energy. Muscles tense, preparing us for quick movement, stillness, or physical confrontation. During this process, the amygdala suppresses functions like digestion, redirecting energy to more immediate needs. It stimulates the release of adrenaline and cortisol, hormones that boost energy levels and sharpen focus. Sweating begins to regulate body temperature during heightened activity.

Importantly, the fight or flight response involves a temporary disconnect from the frontal lobe, where logic and rational decision-making occur. Instead, we rely on instinctual responses rather than reasoned judgment. This rapid and automatic sequence of events occurs without conscious awareness, priming us to react swiftly in threatening situations.

In the face of danger, individuals typically have five primary options:

Flee: Escape from the threat as quickly as possible to ensure safety.

Freeze: If unable to flee, remain perfectly still to avoid detection.

Fight: Confront the threat head-on, utilizing heightened energy and strength.

Fawn: Attempt to appease or befriend the threat, hoping to avoid harm.

Flock: Seek safety in numbers by joining others, increasing the chances of survival through collective defense.

These responses reflect instinctual survival strategies aimed at maximizing safety and survival in the face of danger.

Dr. Daniel Siegal gives an explanation of the brain and trauma responses in the following clip.

What happens to your brain during and after a traumatic event?

During a traumatic event, the brain's processing of information undergoes significant alterations. As the frontal cortex becomes less effective, the brain may lose its ability to perceive the chronological passage of time. Consequently, memories of traumatic events may be stored in a non-chronological manner. Additionally, the aspects of the event that trigger the fight or flight response are more deeply encoded in the brain compared to other details. This prioritization occurs unconsciously, as the survival brain determines what is essential to focus on during the traumatic event.

Moreover, individuals may enter a state of "auto-pilot" or dissociation during traumatic experiences. This serves as a survival mechanism to detach from the immediate threat and navigate through the situation. These automatic responses are often learned behaviors ingrained through socialization and become reflexive actions. For example, a woman facing the threat of sexual violence may engage in people-pleasing behaviors, such as smiling, nodding, or laughing at jokes, to appear at ease externally. However, internally, she may be experiencing extreme fear, with her brain activating these automatic responses to ensure safety.

Following a traumatic event, the brain seeks cues indicating a return to safety. It aims to discharge the energy generated during the event and to seek safety and connection. If this process is disrupted, or if individuals are unable to find safety or connect with supportive individuals, the brain may struggle to close the stress cycle. In such cases, individuals may feel stuck in a state of heightened arousal. Since the amygdala lacks a sense of time and space, reminders of the original traumatic event can trigger signals to the brain and body, inducing a fight or flight response as if the event were recurring.

This 2:00 minute video shows the process of a polar bear completing a stress cycle with some neuroscience commentary. While no polar bears are hurt in this clip, it does show a polar bear being hit by a tranquilizer for research purposes. This video may be sensitive to watch for some individuals.

What happens when your brain develops in an unsafe place?

Growing up in an unsafe environment can distort our perception of safety. Paradoxically, we may feel more secure in unsafe settings and uneasy in safe ones.

As the brain continues to develop, it forms and strengthens connections from the brainstem to the frontal lobe. However, chronic trauma can disrupt these connections, hindering their development. Conversely, connections between the brainstem and the limbic system become excessively developed and hyperaware in individuals experiencing chronic trauma. Brain scans of people with PTSD reveal noticeable differences, including increased activity in the limbic system compared to those without PTSD. Moreover, individuals raised in traumatic environments often exhibit reduced grey matter in brain regions responsible for emotional regulation. These alterations in neurodevelopment persist across the lifespan, leading to heightened amygdala reactivity and changes in brain function.

In essence, if one constantly faces threats to emotional or physical safety the connection between the amygdala and brainstem becomes overly strong and sensitive, while the link between the brainstem and frontal lobes weakens. Consequently, individuals may struggle to differentiate between safety and danger when safety and connection are scarce or when the source of safety resembles the perceived threat.

Your brain is trying to help you!

During a trauma response like fight or flight, our brain perceives imminent danger. It's crucial to understand that trauma is stored not just in our brain but also in our body. Even if we can't recall specific details, our body still reacts to triggering stimuli beyond our control. Healing from trauma involves acknowledging and accepting what happened: "this happened, it happened to me, and it's over now." Achieving this often requires processing through stress cycles by allowing ourselves to fully experience our emotions. Furthermore, it necessitates corrective experiences—seeking comfort and connection. This process can feel daunting, especially for those accustomed to danger and detachment. Teaching our brain to differentiate between safety and danger is essential, reassuring it that we are now safe. Seeking support from a trusted mental health professional with expertise in trauma can be invaluable in this journey.

Take Care,

Kaylee Rudd, LMFT

Resources and Further Reading

Traumatic stress: effects on the brain

The Development and Shaping of the Brain

What Happened to You? Conversations on Trauma by Dr. Bruce Perry and Oprah Winfrey

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind and Body Healing in Trauma by Dr. Bessel A van der Kolk